La isla re-tratada: fotografías de Raúl Cañibano

- Willy Castellanos

- Sep 12, 2020

- 14 min read

(Publicado en el libro “Raúl Cañibano”: PhotoBolsillo. La Fábrica, Madrid, 2012.)

Por Willy Castellanos y Adriana Herrera

Raúl Cañibano nos sumerge en las aguas de lo humano de tal modo que nos hace vivir aquel poema de Nicolás Guillén que clama: «Mire usted la calle. ¿Cómo puede usted ser indiferente a ese gran río de huesos, a ese gran río de sueños, a ese gran río de sangre, a ese gran río?». En su larga jornada como fotógrafo documental por las calles de esa Habana deteriorada y sin embargo intacta en su fascinante vitalidad, o a través de la isla y sus campos poblados de asombro, su mirada ha recobrado un modo de representación que es inseparable de la ontología de lo cubano, pero a la vez, capaz de alcanzar la resonancia —y el conocimiento— de ese gran río en el que transitan todas las gentes. Quizás porque el mismo fotógrafo se parece al “hombre simple” de Guillén, que sabe “andar mirando a todo el mundo, hablando a todo el mundo, el mundo universal que no nos pide nada”.

Sin embargo, ese conocimiento abierto es, por naturaleza, distante de aquel otro registro que en los años sesenta alimentó la iconográfica épica de la Revolución Cubana: primero a través del retrato de sus líderes y de las grandes concentraciones populares, y luego, a partir de una visión idealizada de obreros y campesinos que en los años subsiguientes se impuso como metonimia del «hombre nuevo» y como estereotipo de lo fotogénico en el registro documental. Pero los años setenta también llevaban consigo, bajo la epidermis, la crisis del paradigma representativo de la fotografía documental de aquellos primeros años. Desde el recurso de la sugerencia y, posteriormente, desde el uso recurrente de una metáfora incisiva, otros fotógrafos documentaron la ausencia o lo paradójico como formas de proyectar una realidad social que se apartaba del archivo heterónomo existente. La representación del ser humano se tornó elusiva, y la indagación fotográfica en los desafiantes años ochenta, se abrió, al tiempo, hacia nuevos sistemas conceptuales.

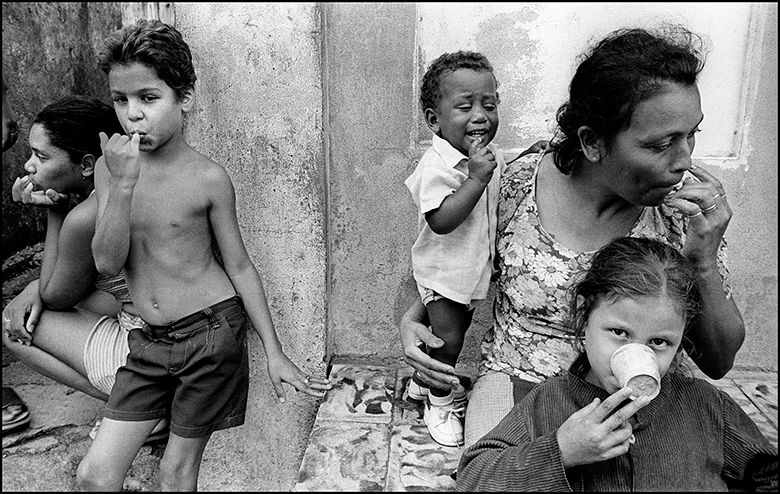

La mirada de Cañibano redefinió la imagen del hombre común desde una tradición documental compleja, desplazando el registro de lo cotidiano hacia zonas o espacios no contemplados por la visión heroica del sujeto como ser social. Su cámara no persigue líderes ni figuras emblemáticas, sino a la gente anónima que transita las calles, o a los habitantes de las tierras guajiras a quienes retrata con la descarnada mirada de lo real cotidiano, sin otras maravillas que las creadas por la complicidad y la convivencia temporal. Asumiendo el errar en la urbe y el viaje al campo como método de trabajo, construye una fenomenología de la cotidianidad en una Cuba sin metáforas, con un ojo capaz de captar lo extraordinario en el instante común, y de crear, al mismo tiempo, una experiencia de cercanía con el espectador. Sus series ensanchan el espectro de la tradición documental en la isla, rescatando las infinitas expresiones de la relación individual con los otros, sin distinguir fronteras entre espacios públicos y privados.

La fotografía antropocéntrica de Raúl Cañibano entiende al ser humano (niño y niña, mujer, travesti, adolescentes o ancianos de ambos sexos) desde el vastísimo registro de cuanto le constituye y le hace tan común como único; tan poderoso como vulnerable; tan cómico como trágico o tan solitario como solidario. Un registro que de igual forma genera una respuesta emocional que puede ir desde la ternura y la compasión hasta el escándalo o la distancia irónica, y que, sobrepasando la multiplicidad que es capaz de abarcar, nos lleva a descubrir que ningún extraño es del todo ajeno a lo que somos. Las fotografías de Raúl Cañibano contienen una lección de proximidad que escapa al quemante sol de las ideologías y a la sombra del tiempo: alumbran la condición humana y el vínculo que nos anuda a los otros.

La Habana; “ciudad de las ventanas abiertas”

En torno a la representación fotográfica de La Habana, existe una infinidad de referencias. A Cañibano le interesa su arquitectura en tanto pueda dialogar con el ser humano. La metrópoli surge como espejo de los deseos para el lente voyerista que persigue el libre vagabundear del prójimo con su carga poética: es La Habana en tiempos del ocio, un espacio en el que caben el festejo, el amorío, el descanso, y los gestos cotidianos de la convivencia. El fotógrafo puede atraparlos en los imprevisibles escenarios de la calle o en interiores que a veces escudriña, a la luz de las velas. Su cámara errante merodea a menudo en el litoral Habanero y en el muro que lo delimita: el omnipresente Malecón, que también es una frontera del no-tiempo, un espacio de deshoras, de encuentros y desencuentros, y en cuyos alrededores las escenas se multiplican a veces teñidas con esa aureola que hizo sentir a André Bretón –entusiasmado con los óleos de Wifredo Lam–, el magma de un territorio surrealista.

Mito y realidad

Series como Ocaso y Fe por San Lázaro reformulan el imaginario de dos segmentos históricamente sensibles a la retórica del documentalismo oficial, y a un exotismo ya universal, anclado en la historia y la iconografía fotográfica del subdesarrollo. Ocaso registra la sobrecogedora soledad y el abandono de la vejez en Cuba, sugerida como metonimia de las propias grietas del sistema. Captadas en una institución médica o en las calles de la capital, las imágenes exploran una faceta poco divulgada, aunque bastante visitada por otros documentalistas cubanos en los noventa. Cañibano acepta el desafío de esta retórica y registra un emotivo documento social, de profundo alcance humano. Resuelta con la elegancia de la madurez visual, Ocaso se impone como una experiencia cognoscitiva muy cercana a la catarsis. La serie trasciende el sentido de cada escena particular, esbozando el relato de un mundo alienado por la indolencia social. Es una visión pesimista, sin duda, pero a la vez, un testimonio que rescata el valor excepcional de esos gestos individuales que reafirman la vida en su inquebrantable dignidad.

Una exploración análoga del drama social ocurre en Fe por San Lázaro, una serie que ahonda en la pervivencia del sentimiento religioso en Cuba, en nuestros días. Cada 17 de diciembre, miles de devotos se congregan en la Ermita del Rincón, a escasos kilómetros del poblado de Santiago de Las Vegas, para rencontrarse en procesión penitente con una de las figuras más veneradas en la isla: San Lázaro, el mendigo de la parábola de San Lucas, o Babalú Ayé en la Santería, dueño y señor de las enfermedades contagiosas y protector de los enfermos.

Las fotografías de Raúl Cañibano abren un paréntesis de elocuencia narrativa sobre el tema. El conjunto elude la secuencia lógica de causas y efectos, pero logra una singular coherencia gracias al poder sugestivo de un encuadre cerrado e intelectivo, que funciona como elemento unificador del relato. Esto le confiere a Fe por San Lázaro un marcado espíritu cinematográfico. En ciertas imágenes, la ambigüedad de la representación actúa como catalizador de las más variadas interpretaciones. Algunas escenas recurren a paradójicas coincidencias: situaciones demasiado fortuitas para ser obra del azar, o demasiado auténticas para ser productos de la manipulación. Entre todas, sintetizan esta legendaria peregrinación de penitentes, cuyo único deseo es devolverle al Santo –con las monedas de la devoción–, el milagro de los favores concedidos.

La fotografía como ejercicio de convivencia

Cien años de soledad, obra cumbre de la literatura latinoamericana, surge del viaje que llevó a García Márquez de regreso a la tierra del origen muchos años después, y del consecuente deseo “de dejar constancia poética del mundo de mi infancia”[4]. De modo paralelo, Raúl Cañibano sintió el llamado de la Tierra guajira donde vivió una parte de su niñez, en el ingenio Argelia Libre del poblado de Manatí, en la provincia de Las Tunas.

Tierra Guajira se inspira en un retorno que es tan geográfico como afectivo, dando origen a la más lírica de sus series y también, a la que define en su proyecto creativo, al viaje como método y a la fotografía como ejercicio de convivencia humana y estética.

Algunos fueron viajes muy difíciles –comenta el autor—, en otros, tuve la oportunidad de entablar amistad con los campesinos y quedarme en sus casas por días, compartiendo también sus carencias (…). Son personas muy nobles y comparten lo poco que tienen. Yo les ayudaba llevándole ropas de trabajo y herramientas que conseguía en La Habana. Así viajé de pueblo en pueblo, primero por la ruta Martiana de Playita a Dos Ríos, y luego por todo el país: Gibara, Remedios, la Ciénaga, Consolación del Sur o La Isla de la Juventud.[5]

Realizada como ensayo a largo plazo, Tierra Guajira contiene la poética de una alianza indisoluble entre la tierra como fuente de vida, el hombre que la trabaja y los animales que la habitan. Es una mirada descarnada –como la vida en el campo−, pero capaz de registrar la sensibilidad del guajiro a través de su ritualidad diaria, ya sea en el trabajo, las celebraciones, o en la intimidad de esos hogares de puertas perenemente abiertas. Tanto las imágenes urbanas como las rurales, son tomadas en su mayoría en momentos de ocio –ese espacio ignorado por la tradición documental que le precedió−. Pero mientras en las escenas de la ciudad se advierte una atmósfera de aislamiento y fragmentación, en el campo predomina una unidad interior que proyecta el imaginario de un mundo apacible, sin fisuras. Así, el trabajo simultáneo del fotógrafo en ambas series establece un contrapunto revelador, tanto en lo estético como en lo sociológico.

Es muy posible que las fotografías de niños y niñas funcionen como autorretratos, en un intento por rescatar las huellas de una infancia borrosa en la memoria del autor. Confabulándose con sus juegos, Cañibano capta una lúdica poderosa capaz de doblegar la realidad, recreando una instancia particularmente bella de su relación con los animales; un vínculo construido sobre la certidumbre de que, no es posible la vida de un reino sin el otro. Si «la literatura es la infancia al fin recuperada»[6] como plantea Georges Bataille, Tierra guajira es entonces el documento de un rescate entrañable: el relato en imágenes de un espacio perdido que regresa en el tiempo, a través del asombro y del prisma de los ojos del niño que fue.

[1] Molina, José Antonio. Entrevista personal. Marzo de 2011. [2] Cernuda, Luis. Luz y cielo de La Habana. https://www.worldliteraryatlas.com/es/quote/luz-y-cielo-de-la-habana [3] Jamís, Fayad. https://hoteltelegrafo.blogspot.com/2019/08/23-y-12_12.html [4] Apuleyo Mendoza, Plinio. El olor de la guayaba. Conversaciones con Gabriel García Márquez. ttp://LeLibros.org/ p.56. [5] Entrevista personal con el artista. Enero de 2012. [6] Traducción libre de la frase original de Geoge Bataille: “La littérature, je l'ai, lentement, voulu montrer, c'est l'enfance enfin retrouvée”. http://quilesfrederique9.e-monsite.com/pages/dossiers/georges-bataille.html

The Island Re-Portrayed: Raúl Cañibano’s Photographs

(Introductory essay for the book “Raúl Cañibano”: PhotoBolsillo. La Fábrica, Madrid, 2012.)

Translation: by David Alan Prescott.

By Willy Castellanos and Adriana Herrera

Raúl Cañibano immerses us in the waters of the human in such a manner that he makes us lives out that poem by Nicolás Guillén that exclaims: “Look at the street. How can you be so indifferent to that great river of bones, that great river of dreams, that great river of blood, that great river?”. In his long journey as a documentary photographer through the streets of that Havana that is deteriorated yet intact in its fascinating vitality, or into the island and its fields populated with amazement, his gaze has recovered a manner of representation that cannot be dissociated from the ontology of the Cuban; a knowledge that is as particular as it is universal of that great river of men of all time.

However, that knowledge which is open by nature is different to the other one that was at the heart of the epic iconography of the Cuban Revolution. Firstly, through the portrait of its leaders and major popular concentrations; and then, through an idealized view of workers and peasants which in the so-called “Grey Period” stood out as a metonymy of the people in the construction of the “New Man”. The end of the seventies brought with them, below the skin, the crisis of the representative paradigm of the documentary photography of those romantic years. With recourse to suggestion and then through the recurring use of an incisive metaphor, other photographers have portrayed absence as a way of projecting a reality that moved away from the existing heteronymous archive. Representation of the human being became elusive, and photography, beneath the artistic indignation of those lucid years, opened up to new conceptual systems.

Cañibano’s gaze redefined the image of the common man through a complex documentary tradition, shifting the concept of reality towards areas that were not stamped with the heroic view of the person as a social being. His camera does not follow leaders nor emblematic figures, but rather anonymous people who go by in the streets, and the men and boys of the countryside whom he portrays with the stark complicity of the real. He accepts his position as a wanderer through the city and the journey to the countryside as a method, constructing a phenomenology of daily life in Cuba without metaphors, like an eye capable of capturing the extraordinary in the common instant and of at the same time creating an experience of nearness in the spectator. His series broaden the spectrum of the documentary image, recovering the infinite expressions of the individual relationship with the others, without distinguishing frontiers between public and private spaces.

His anthropocentric photography goes to the generic man (boy and girl, woman, cross-dresser, adolescents or old people of both sexes) from the extremely vast register of what makes him up and makes him as common as he is unique; as powerful as he is vulnerable; as comic as tragic, as alone as social; a register that also generates an emotional response that may go from tenderness and compassion to scandal or ironic distance, and which, surpassing the multiplicity and complexity that it is capable of containing, leads us to discover that no stranger is totally alien to what we are. Cañibano’s photographs contain a lesson of proximity that goes beyond the scorching sun of ideologies and the shade of time: they enlighten the human condition and the link that ties us to others.

The City of the Open Windows

There is an infinite quantity of references around the photographic representation of Havana. Cañibano is interested in its architecture as it dialogues with the human being. The city emerges as the mirror of desires for the voyeuristic lens that follows the free wandering of the next person with its poetic charge: this is the Havana in times of leisure, where there are festivals, romance, rest and the gestures of socialization. He can catch them on the invisible stages of the street or indoors where he sometimes peers in by candlelight.

His wandering camera often prowls the coast of Havana and the walls that bound it: the omnipresent “Malecón”oceanside walkway which is also a frontier of non-time, a space of unearthly times, of meetings and missed meetings, around which the scenes are multiplied and often tinged with that aura that made André Bretón, who was passing through the city, feel like he had entered surrealist territory. Cañibano seeks repeated forms, creators of rhythms, right where daily life reaches a mode of intensity without myth. In that “City of Columns”, the passage of time favors narratives in bulk. Havana is superb in its deterioration and is generous to excess in decisive instants that the photographer steals from life. Taking advantage of the order of the coincidences, he creates parallels in scenes that are appetizers to multiple potential readings, uniting situations that may have a relationship of stating or of contradicting through the conceptual charge of the image. In this manner he reconstructs life – like Joyce did in his native Dublin – through a visual approach that captures the chaotic convergence of the urban experience using the simultaneous nature of dissimilar situations.

Cañibano’s gaze travels through the open city revealing its spaces, feeding off the histrionic feeling of the Cuban who, as the critic Juan Antonio Molina once said, gives himself with glee to the pose and the theatrical game[1]. One loves Havana, although it is no longer like when Luis Cernuda saw it, “beautiful, aerial, airy, a mirroring”[2]; and because for each Havana resident it is still the “city with most open windows”, as Abilio Estévez wrote in his “Inventario secreto de La Habana”; or, just as Fayad Jamis lived it: “This is perhaps the true center of the world”[3].

Myth and Reality

Series like “Ocaso” [Sunset] and “Fe por San Lázaro” [Faith for St Lazarus], reformulate the imaginary of two of the segments historically sensitive to the rhetoric of the press, and to an exoticism anchored in the photographic iconography of underdevelopment. “Ocaso” registers the overwhelming loneliness and abandoning of old age in Cuba, as a metonymy of the cracks in the system. These images taken in an institution or in the streets of the capital explore a facet that is not often shown but which was often visited by other documentary photographers of the nineties. Cañibano accepts the challenge of this rhetoric and constructs an emotive social document with a strong human impact.

Brimming with the elegance of visual maturity, “Ocaso” stands as a cognitive experience that works through catharsis. The series transcends the meaning of each initial shot, drawing out the tale of a world alienated by social indolence. It is a pessimistic view, but which brings out the exceptional value of the individual gestures that restate life in its unshakable dignity.

An analogous exploration of the drama takes place in “Fe por San Lázaro”, a series which delves into the survival of religious sentiment in Cuba. Every 17th of December thousands of devout worshippers congregate at the Rincón Hermitage, a few kilometers away from Santiago de Las Vegas, in order to form a penitent procession with one of their most revered figures: not Lazarus, the resurrected, but the beggar in the parable in St Luke, Babalú Ayé in the Afro-Cuban religion, lord and master of the contagious diseases and protector of the sick.

Cañibano’s photographs open a parenthesis of eloquence on this subject. The set eludes the logical sequence of causes and effects, but it manages to achieve a unique coherence thanks to the suggestive power of the close up. This grants “Fe por San Lázaro” a clear cinematographic spirit. Certain images come apart in ambiguities and are then brought together again in the spectator’s reading. Some resort to paradoxical coincidences, situations that are too fortuitous to be the work of chance, and too authentic to be the product of manipulation. All together, they synthesize that legendary pilgrimage of which the only purpose is to return the miracle of favors granted to the saint, through the coins of devotion.

Photography as an Exercise of Socialization

“One Hundred Years of Solitude”, one of the most important books in Latin-American literature, arises from the journey that took García Márquez, many years later, back to the land of his origin and to the desire of “leaving poetic constancy from the world of my childhood”[4]. In a parallel manner, Cañibano felt the call of the “Tierra guajira” [Guajira Land] where he lived a part of his childhood in the Argelia Libre sugar mill in the town of Manatí, in the province of Las Tunas. “Tierra guajira” is inspired by that return, which is as geographical as it is affective, giving rise to the most lyrical of his series, and that which defines the journey as a resource, and photography as an exercise.

“Some were very difficult journeys,” he comments, “and on others I had the opportunity to strike up friendship with the peasants and stay in their houses for days, sharing their shortages (…). They are very noble people and they share what little they have. And I helped them bringing them work clothes and tools that I got in Havana. I thus travelled from town to town, first along the Martiana Route, from Playita to Dios Ríos, and then all throughout the countryside: Gibara, Remedios, la Ciénaga, Consolación del Sur and La Isla de la Juventud.”[5]

The series was carried out as a long-term essay and contains the poetics of an unbreakable alliance between the soil as the source of life, the man who works it and the animals that live on it. It is a stark gaze – just like life in the countryside – but one which registers the sensitivity of the country peasant through his daily ritual activity, whether at work, at celebration, or in the intimacy of those homes with their doors always open.

Both the urban images and the rural ones are mainly taken of moments of leisure – that space ignored by the photography that preceded him. But while in the city one can sense an atmosphere of isolation and fragmentation, what predominates in the countryside is an inner unity that projects the imaginary of a pleasant world, without any ruptures. Thus, the photographer’s simultaneous work on both series establishes a revealing counterpoint on the aesthetic and sociological level.

It is very possible that the photographs of the boys may function as self-portraits, in an attempt to bring back the marks of a childhood blurred in memory. In conspiring with his games, the photographer captures a playful power capable of bending reality and recreates a particularly beautiful instance of his relationship with the animals, built on the certainty that the life of one realm is not possible without the other one. If “literature is childhood finally recovered,”[6]as Georges Bataille states, Raúl Cañibano’s photography is the idyllic recovery of that “Tierra guajira” by means of a camera that looks at reality with the eyes of the child he was and gives him back his innocence.

[1] Castellanos, Willy. Personal interview with Juan Antonio Molina. March 2011. [2] Cernuda, Luis. Luz y cielo de La Habana. https://www.worldliteraryatlas.com/es/quote/luz-y-cielo-de-la-habana [3] Jamíd, Fayas. https://hoteltelegrafo.blogspot.com/2019/08/23-y-12_12.html [4] Apuleyo Mendoza, Plinio. El olor de la guayaba. Conversaciones con Gabriel García Márquez. ttp://LeLibros.org/ p.56. [5] Castellanos, Willy. Personal interview with the artist. January 2012. [6] Free translation of the original sentence by Geoge Bataille: “La littérature, je l'ai, lentement, voulu montrer, c'est l'enfance enfin retrouvée”. http://quilesfrederique9.e-monsite.com/pages/dossiers/georges-bataille.html

Comments