Exodus Alternate Documents

Centro Cultural Español de Miami (CCEMiami) | Oct-Nov., 2014

Exhibition View

Exhibition Statement

Exodus, Emigration, and the Recovery of Collective Memory

By Adriana Herrera and Willy Castellanos

Exodus: Alternate Documents, is a project of reflection on the phenomenon of emigration and large human displacements. The proposal of the Aluna Curatorial Collective (Adriana Herrera and Willy Castellanos), is part of the creation of an interactive space that breaks the limits of documentary record, transforming it into an open exercise for the recovery of collective memory. This exercise involved the participation of the Cuban immigrant community in Miami, as well as of the protagonists of the 1994 “Exodus of the Rafters.”

Between August and September of 1994— in what constituted one of the most dramatic episodes in contemporary Cuban history—more than 35,000 Cubans embarked for the United States in precarious boats built with their own limited resources. Designed as a laboratory or a relational workspace that combined artistic and documentary practices, Exodus: Alternate Documents aimed to create a new type of information—content alternative to the original document—that was capable of opening new and unpublished routes to redirect the traditional story about the Crisis of the Rafters in Cuba. The exhibition involved the active participation of the public. The testimonies, memories, and life stories of the participants of the exodus were recorded through various installations and events in order to reconstruct a lost page of history.

Photographs, participatory installations, and video projections made up this exhibition, which was also a tribute on the twentieth anniversary of the crisis to all those who, in the most diverse latitudes of the world, embark every day on the uncertain path of emigration. A video booth was set up to film the testimonies of those interested in the reconstruction of the event from their own experiences. In addition, calls for submissions and other public events were organized. The materials collected during the days of the exhibition will be used for the production of new dialogues on the subject and remain in Aluna Art Foundation’s archives at the disposal of creators and interested institutions.

Exodus: Alternate Documents takes as its starting point the presentation of first-hand historical material: a collection of 80 photographs taken by Willy Castellanos on the coast of Havana during the events that led to the “Exodus of the Rafters” in 1994. Unlike other images published by the international media, Castellanos' photographs record the departures on the coasts of Havana and could well be presented, given their testimonial and aesthetic value, as an exhibition per se. But the artist also displays acoustic installations such as Dry-Feet-Wet-Feet, documentary videos, and participatory works such as Cabina, Album, Requiem, and Water, proposing them as bridges to new content that is not implicit in the stories of the 1994 photographic record. The videos presented included stories and interviews filmed recently, both in Havana and Miami, and make up two complementary thematic segments of the exhibition: On the Quest to Find Those Photographed in 1994, and Memories of the Crossing.

Additionally, suggestive installations were presented by two Cuban-American guest artists: Juan-Sí González and Coco Fusco. González works with different media, from photography and installation to video and performance. His installation Rosa Náutica is made up of a salt screen onto which is projected a selection of videos of the empty rafts found adrift in those tragic days of 1994. Coco Fusco is an essayist, curator, and interdisciplinary artist. Her installation Y el mar te hablará (“And the Sea Will Speak to You”) invites the audience to share an unusual physical and emotional experience: the experience of traveling from Cuba by sea. Participants were invited to leave all their possessions (wallets, money, phones, watches etc.) before entering the dark theater. Traditional seats were replaced by inflated rubbers, the same ones that rafters usually use on their boats.

Exodus: Alternate Documents was a joint effort of the Spanish Cultural Center of Miami (CCEMiami) and Aluna Art Foundation, with the collaboration of the Cuban Museum Miami and its “Sweet Home” program (Knight Foundation). The event was supported by El Nuevo Herald, The Miami Herald, and The Cuban Research Institute (FIU), and received the award for the Best Cultural Event of the Year, granted by the Arts Miami Foundation.

Exodus: Alternate Documents

Willy Castellanos

Guest artists: Juan-Sí González and Coco Fusco

A communitarian and interactive Project curated by Aluna Curatorial Collective (Adriana Herrera and Willy Castellanos).

From September 12th to August 31st, 2014

Centro Cultural Español de Miami (CCEMiami)

Works

Dry Feet/Wet Feet (Installation), 2014

Installation Soundtrack:

Documentary audio record of a group of “Balseros” (rafters) living Cuba in August 1994 | Courtesy of Caiman Productions

Dry Feet/Wet Feet, 2014

Installation with sound, 28’ L x 9’ H| Photos printed on fabric, acrylic boxes, water, sand, steel wires and industrial tensioners. Documentary audio record of a group of Rafters living the island, courtesy of Caiman Productions.

The “Wet Feet/Dry Feet policy” is the name given to a consequence of the 1995 revision of the “Cuban Adjustment Act” of 1966, that essentially says that anyone who fled Cuba and got into the United States would be allowed to pursue residency a year later. After talks with the Cuban government, the Clinton administration came to an agreement with Cuba that it would stop admitting people found at sea. Since then, in what has become known as the "Wet Feet/Dry Feet policy, a Cuban caught on the waters between the two nations (with "wet feet") would summarily be sent home or to a third country. One who makes it to shore ("dry feet") gets a chance to remain in the United States, and later would qualify for expedited "legal permanent resident" status and eventually U.S. citizenship.

From 1995 to January 2017 (year in which it was revoked), this law regulated the arrival of all those Cubans who jump into the sea in precarious boats, in what constitutes a regional tragedy that also affects thousands of Haitian and Dominican citizens.

Alternate Documents (Poliptych), 1994-2014

01/08 The Threat

Shooting with a telephoto lens is to scrutinize the other’s intimacy, to participate in a story to which you have not been invited, or asked to coexist in. Those photographed can’t perceive the photographer, who exists in a fictional dimension of reality, a false proximity that is purely optical. If image reconstructs history, how many of these “interferences” make up the documents that we have of things today? Is photography an instrument of colonization, a way to appropriate intimate space and convert it into editorial material to be consumed and transmitted?

I quote a phrase by Mario Bellatín, as an imposition of silence: “Never has so much been seen as when photography disappeared.” At the same time, I see in this photo a myriad of images: Gericault and his “Medusa”, Heyerdahl, the Argonauts… I look through a prism that overlaps that which is distant and that which is close, but also fear at the threat of death and fascination for the epic of those who face it in extreme situations.

02/08 The Battle of the Stowaways

I usually think about “Blow-Up”, Cortazar’s story, when I see the pictures of that heavy night in ’94. I photographed “blindly”, guided by the flash that illuminated the coast at fractions by the second. Behind the dark veil, I heard the creaking of the wood, and the sound of the sea in the frenzy of the crowd. It was only days later, when I printed the negatives, that I visualized the real extent of the chaos. The image moved me, and my surprise was even bigger when I saw, between all those people, one of my childhood friends, who had been missing for months. Had he given up the journey –as he later told me- or was he simply one of the many stowaways that tried to board the ship? Random, contingency, causality… what keys moderates the eventuality of photographs? Who owns these images? The operator who surprises –by pure luck- the moment, or the subjects that stage a drama that marks them for the rest of their lives?

03/08 The Blue Wall

For those of us born in the city of Havana, and perhaps for almost every Cuban, the sea is an obsessive constant. The sea surround and define us. Its omnipresent aroma be- comes entrenched in our memory. The sea limits us, the sea wall is in…, the Blue Wall.

Then, there are the ships than dock and cast off. Cuba is a necessary stop; a crossroad opens to all destinations. People who come and go. Spanish Caravels, English masts and canons, slavers and pirate ships. Steamships packed with Europeans; foul holds crammed with Asians. American cruise ships, Soviet freighters, border patrol boats and also…, rafts. Slight and fragile, made of old planks and tattered sails. Rowing and riptides, Blessed Virgins and holy cards. Rafts that break through the wall on the foamy crests of waves, some on top, under the searing sun, in the breeze and the uncomfortable feeling of salt residue on one’s skin. Rafts that set out without a return ticket; too little island for so much searching, too many dreams for so much sea.

04/08 The Visitor

Someone wrote that these photographs were a premonition of my own leaving. “Why didn´t you go on a raft back then?”, they asked me. I guess I chose to stay and describe the exodus experience of my own people in these pictures that, in some way, are illegible or transmit the opacity of their own circumstances. Why is this man adrift as if he was accompanying a friends’ raft as a leisure activity? That seemingly absurd gesture is indecipherable.

I read a Feuerbarch’s quote which anticipates Benjamin: “For the present age which prefers the sign to the thing signified, the copy to the original, fancy to reality, the appearance to the essence, illusion only is sacred, truth profane.” Perhaps the act of turning a human experience that is unspeakable and untransmissible in to “a mere image”, is a way of desecration. And yet, from all the nonsense that passes through this photo and the act of taking it, there is a remnant for which I still believe it to be necessary.

05/08 Document/Fictions

Document/Alternative fictions. I can´t reconstruct a credible story about this photograph that doesn´t come from my fictions. There is missing information, perhaps more precise elements or situations. It lacks contextual references, and other necessary data to reconstruct the paradigm of the photographic; or rather, to stage the event from a documental logic. It´s these images that need (like crutches) other contiguous images, or perhaps a text, like the one I am writing now, to give them some meaning.

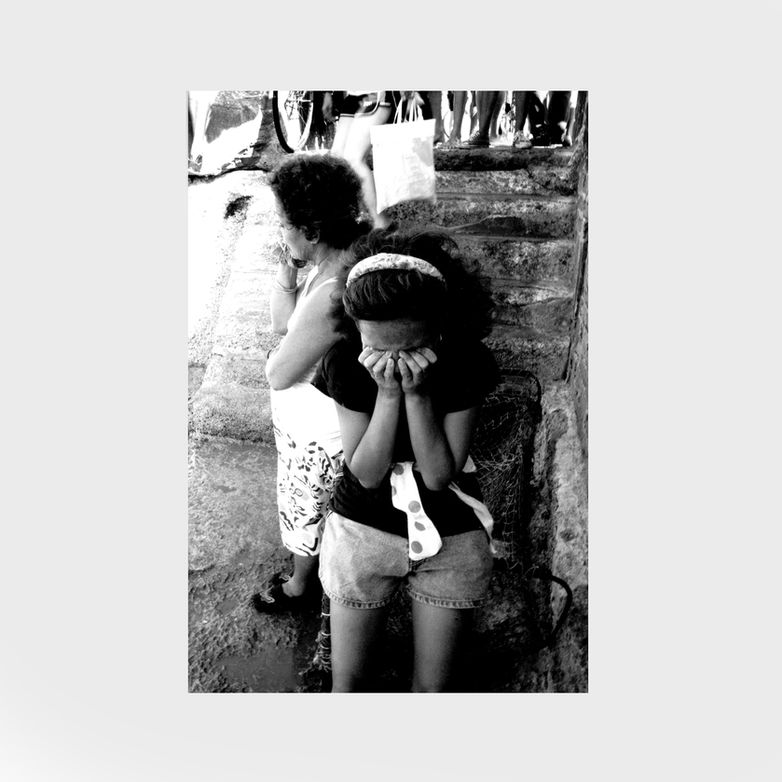

Maybe this photograph will not be published in the press, but it still fascinates me. The girl´s serene look captivates me, her bold attitude towards the camera, and the intruder who carries it. Did she travel in the reckless draft inflated by illusions? I think now, years later, that she stayed in the island, that that afternoon she was just going along with her family for the goodbyes. If this photograph is anything, it is the document of my fictions: An open notebook of an unfinished story, where no possibility is definite; a story lost in the limbo of memory and reality.

06/08 Subversion/Repression

How is it possible to situate oneself at the center of such evident antagonism? Very simply: Take out a camera and point it towards the people, in the vortex of an event that´s “sensitive” to the status quo and its definitions. That, perhaps, is the only thing that this picture couldn´t capture on that August morning, where a broken raft hit the shore as a policeman barged into the scene, unexpectedly. The camera documented the return, but not the discourse of the looks that were exchanged, or the implications that situated the photographer at the center of this contradiction. The picture didn´t catch the policeman´s severe look, nor the “unspoken” words of repression (in what foreign magazine would they publish these pictures?); it also didn´t catch the fear and the mistrust of subversion (in what official archive would my face end up.)

In this way, the image is the portrait of the absence of the photographer: The portrait of an “off-screen” – not being in the frame- moment that ended up making me into a “person to distrust.”

07/08 North Bound

The global village has situated its abundance poles in the northern hemisphere, mobilizing in this direction the incessant flux of the less fortunate. If utopic impulse unleashes the passage points –like an irresistible compass- to this hemisphere, disillusion and its sunken ships become “no-man’s lands”, in frontiers to be overtaken. In this way, Tomas More’s island seems to still be sailing adrift, in an imprecise point of the sea of resignation.

But in what latitudes do the images, the photographs, move? Towards the epicenters of power and their stories, or towards the south, to the frontiers of dystopias and their rebellions? Towards the margins of those small stories (like in this picture) that are woven in secret and inserted like nails into the anonymous archive of everyday life? Documents, testimonies, evidence…what notions intervene in the construction of the immovable concept that we call “History”? Who writes the great tales of human experience, and what episodes are included in this narrative of knowledge destined for consumerism and divulgence?

08/08 The Heritage

I took this photograph off the coast of Havana during the Exodus of 1994. In the scene, a young ‘Balsero’ offers up his sandals to a friend before he embarks north. The young man thought he would not need them at sea and that, once in the United States, he could buy new ones of better quality. This is my interpretation of the scene, though I cannot as- sure you that my story is true. A few minutes later the group dispersed, and I could not get more information than what you perceive when viewing the picture. In my version of the story, these sandals are an expression of linkage and of an inheritance.

This photograph has been little disclosed. It is a mute file “moving out” of the archive, or inside a “dead” archive (the set of photos that I took that day). Its story does not participate in the knowledge we have of “footwear”, nor in the reconstruction of a notion of history associated with it or with the island.

North Bound: beyond the Blue Wall Series, 1994

Participative installations, 2014

The Wall, 2014 (Video)

Wall, 2014

Video by Manuel Andrés Zapata | 2:14 min.

Photos by Willy Castellanos

References

Exhibition Close-Up: Exodus; Alternate Documents

(Cuban Art News, October 2014)

By Susan Delson

“Curators Willy Castellanos and Adriana Herrera on art, history, and the 1994 rafter crisis | As the exhibition Exodus: Alternate Documents draws to a close this week at the Centro Cultural Español in Miami, we finally caught up with Guillermo “Willy” Castellanos and Adriana Herrera of the Aluna Curatorial Collective for an email conversation about the show. Answering individually and together, they provided a provocative overview of the exhibition and the thinking behind it”.

What was the genesis of Exodus: Alternate Documents? How did it begin?

Willy: Several moments precede the project. The first was the spontaneous photographic documentation I did on the Havana coast in the summer of 1994, during the turbulent days of the “Rafter Crisis.” With no intentions of exhibiting or publishing, the series was built from documentary pictures, a genre that particularly interests me in my studies of art history. I chose 80 images to form the essay North Bound; Beyond the Blue Wall, whose title comes from a short piece I wrote, about three years later, while living in Argentina. The work remained unpublished for nearly twenty years.

Adriana/Willy: In 2012, Aluna Curatorial Collective inaugurated the PhotoAmerica section in the Arteamérica fair with Exodus, a Missing Page in History, an installation of 30 photos. The idea was to insert into the archives of history this version—this “little history”—of the Cuban exodus, and with it try to reference every exodus across the world through these individual accounts. Since then, the project has taken on a more reflexive focus, questioning not only the social and cognitive authority of photography but the very concept of “History” as a single and totalizing narrative.

No less important was the emotional connection we established with people. That small space became an impromptu place for the testimonials of rafters who, in the presence of the images, wanted to tell their stories, and even offered to lend photographs and even objects related to their experiences. It was there that we had the idea of expanding the project.

Willy, your 1994 photos are the core of the exhibition, but it goes beyond that.

Willy: The documentary record of the exodus was only the starting point for the creation of a scenario that would provoke the collective memory. The series that gives title to the project—Alternate Documents, 1994-2012—starts from this paradoxical power of photography to mythify history and at the same time expose the medium’s own contradictions. The photos express "my" version of the events, and at the same time my own inability to know, for sure, what happened there. So, within the limits of the gallery, the exhibition itself is responsible for questioning this authority.

The photos have been presented in two different ways: first, as a documentary record, presented in a traditional way in black-and-white prints; and then in installations with intervening texts, 20 years later. The use of tracing paper in the second presentation reinforces the sense of a "membrane," or layer of meaning, in the process of reconstructing history. The projections that these copies create on the wall evoke for us the contradictions of the image and its alternate versions, the original and the copy, or the picture and its reflection.

The texts that appear as captions demonstrate the inadequacy of visible data and the possibility that any interpretation could be traversed by fictions, tales, and reconstructions of all kinds. In Exodus, the works become the support for the living experience, in a fragmented reconstruction that includes the voices of those who tell their stories or leave traces of them in the exhibition space.

Adriana/Willy: Exodus: Alternate Documents combines artistic and documentary practices. We use live testimonials, photography, and video interviews as documentary genres, and we’ve combined them with video art, artists’ installations, and other installations. This mixture was conceived as a curatorial exercise in the production of meaning and collective intervention.

The project is shown in a gallery with alternative materials, such as industrial cables and struts, used in a work created by the artist Lili (ana), as well as advertising circulars, fabrics and prints on vinyl, tires, and cork boards and white boards for writing. More than an exhibition, the gallery became a workspace open to all rafters. Some works required their participation and will only be completed when the show is finished. In the work Album, for example, we encourage people to leave their own photographs of the exodus. In parallel, we built a one-person room for video-shooting, where it’s possible to record, in private, a personal testimonial. With the support of cultural anthropologist Ariana Hernández-Reguant, we had an open-mike session with a group of rafters, where we recorded their narratives of the journey that will remain as materials in the exhibition.

Two Cuban-American artists, Coco Fusco and Juan-Sí González, were also invited to create installations.

Adriana/Willy: As curators, we’re interested in the convergence of multiple voices and points of view. The idea of building a scenario out of documentary-based works led us to think about an open archive, not formed by a single voice or perspective. We also wanted to include some documentary images taken from different perspectives of space and time.

We had North Bound, Willy’s series of photos taken on the coast off Havana. And also Rosa Náutica by Juan Sí González, which perfectly evokes the experience of one who approaches it from "the other side,” flying with los Hermanos al Rescate (Brothers to the Rescue) over a sea full of rafts, some of them castaways, some marked by death. Rosa Náutica includes the film record of his own volunteer experience in these aircraft, as the record of a poetics so violent as to be deeply moving: the image of a raft that little by little sinks into the sea. The drifting rafts are projected not only on the wall but are duplicated on a surface created from mirrors and sea salt, suggesting the infinite dimension of the ocean. To stand before the scene of a raft covered with water is a way of returning to that moment of actual collapse, a way to obliterate time and look, not an object that disappears, but at the vast odyssey of an exodus that never seems to end. On the opening day, a few steps from the CCE Miami [where the show was presented], a raft from Havana made landfall, unlike others that week, whose bodies were not recovered.

Adriana: Coco Fusco´s installation And the Sea Will Speak to You, creates an immersive environment that dissolves the outside world and the present time. The artist places the viewer—who should remove their personal belongings and go barefoot into the projection space—on the surface of a drifting sea. In that dark space, the "outside" ceases to exist; the only perception is of the film that chronicles the rafter’s journey back to the island. Meanwhile she shares, as if in an intimate diary, the course of her thoughts as she faces death. You cannot see Fusco's film without getting involved in it. The viewer sits not on a chair, but in the inflatable rafts like those the rafters launch into the sea. This experience involves the body of the spectator as an integral part of the work, transported to the drifting sea. The memory comes from a woman who returns to bring back her mother’s ashes.

The experience of watching (and listening to) Willy´s installation Pies secos, pies Dry Feet, Wet Feet is very moving. First, from a distance, your eyes compose and complete the scene of the immensity of ocean. It is composed—according to the Gestalt principle—because the photographs are fragmented by intervals of emptiness, which dilute the images so completely that the initial impulse is to reconstruct the sea on the horizon. A sea with no name that first appears tranquil but seen more closely reveals clusters of incipient storm clouds. The horizon is a vast sea occupying the entire wall, the entire field of vision, but it’s fragmented. Each fragment rests on acrylic boxes forming a sequence of sand and water: dry feet, wet feet. So, the installation shows with formal, almost minimalist beauty, the elements of the exodus: water, absence, horizon, uncertainty, empty, threatening storm, infinitely adrift...

But when the viewer comes closer and is right in front of the installation, what was invisible so far now appears: the acoustic dimension. And the voices of the rafters are heard in the instant that concentrates everything: the moment of departure. It is the sea, interrupted by fragments of emptiness and voices of those who are leaving (and whom we don’t see), and those who have left (and we know nothing about them). All this multiplies the evocative power of the work. The visual evocation has no geographical referents but the aural documentation (by filmmaker Luis Guardia) includes the actual instant of departure and the immense tension between the anxiety of the journey and the longing for what lies beyond the horizon: some place to build life again.

The video Muro (Wall, 2014) by emerging artist and animator Manuel Andrés Zapata contains a poetics that uses two elements in a continuous movement and superimposition: water and stone. His work is based on visual documentation of an extensive wall that Willy shot off the coast of the Mar del Plata in Argentina, for him the place afuera de la isla, away from the island. Photos are an unconscious evocation of what he saw in the sea around the island, with greater intensity than ever when he documented the exodus: a big blue wall.

It’s now 20 years since the balsero crisis. What do you hope the project will achieve?

Adriana/Willy: As a space for interaction and sociocultural resuscitation, we’re motivated by the possibility of extending the margins of public participation, including the expectations usually associated with minorities that are often have little to do with art projects. Our challenge now is to get these people to attend and actively join the project we’ve organized.

The exhibition allows them to reflect about their own history and personal identity. Exodo: documentos alternos attempts to preserve the collective memory of one of the most moving events of contemporary Cuban history, to show that the past is not a closed case but a process that’s constantly being rewritten and reinterpreted. It’s the equivalent, in a practical sense, to returning that power to the voices of people who lived through the events. In this way, from a space of art comes an exercise that reaffirms the value of “small histories” above the official versions inscribed from a base of power and its ramifications.